The vegetation of Homoxi

The vegetation in the Homoxi region is a mosaic of undisturbed and disturbed habitats including terra firme forest, streamside and riverside forests and herbaceous tangles, open areas of gravel and sand with sparse herbaceous or scrub cover, and secondary forests on variable soils resulting either from garimpeiro activity or from Yanomami cultivation. The terra firme forest is by far the dominant vegetation type covering this undulating landscape, and secondary vegetation is almost entirely limited to the bottoms and sides of river valleys.

|

|

Figure 1: Views towards the Homoxi Post from the South (left) and from the East (above) |

The vegetation descriptions that follow are intended as brief characterisations of the main categories that were identified. More detailed lists of the species recorded in each environment can be found in Appendix 2.

Natural environments

Forest

The forest in the Homoxi region is reasonably homogeneous, with a canopy approximately 25-30m high and emergent trees to 40m+. There are relatively few trees over 40cm in diameter, lianas are common, and the understorey is fairly open. In the higher areas (around 1000m) the forest appears to be slightly more open with a lower canopy and fewer large trees, but this has not been quantified. A dense root mat covers the soil surface on the hillsides. Given the undulating nature of the terrain there are also inevitably some differences between the structure and composition of the forest from one area to another, on account of topographic and hydrological variations.

|

|

|

|

Figure 2: Large individual of Cedrelinga catenaeformis in the forest near Homoxi |

Figure 3: Forest on hill top at around 1000m altitude SW of the Homoxi Post |

Among the common and conspicuous canopy tree species are Clathrotropis macrocarpa, Micrandra rossiana, Alexa confusa, Swartzia schomburgkii, Chimarrhis sp., Caryocar pallidum, Dacryodes roraimensis, Ormosia steyermarkii, Eschweilera spp., Pourouma spp., Protium fimbriatum and Pseudolmedia spp. Smaller tree species such as Anaxagorea dolichocarpa, Amphirrhox surinamensis, Duguetia lepidota, D. stelechantha, Mouriri guianensis, Myrcia spp. and Trymatococcus amazonicus are common elements of the understorey. One of the more common emergent trees is the leguminous Cedrelinga catenaeformis, a particularly large individual of which was encountered with a diameter of over 3m.

There are very few large palms in the terra firme forest apart from the occasional individual of Oenocarpus bacaba or (more commonly) Socratea exorrhiza. In the lower understorey, however, they are more abundant, with Iriartella setigera and Geonoma spp relatively common and occasional individuals of Astrocaryum gynacanthum, Bactris corosilla and Hyospathe elegans.

Lianas are relatively abundant in the forest, conspicuous species including Bauhinia guianensis, Pinzona coriacea and Abuta rufescens. The ground layer includes the omnipresent Psychotria poeppigiana, various species of Piper (with P. francovilleanum particularly common), Tabernaemontana macrocalyx, Urera baccifera, a common Anthurium, Heliconia spp. and some Marantaceae (including Ischnosiphon arouma).

Mosses and lichens are abundant on the trunks and branches of the trees, as are a range of vascular epiphytes including Orchidaceae (e.g. Maxillaria spp.), Araceae (including Anthurium clavigerum, Philodendron hylaeae, Heteropsis steyermarkii, Cyclanthaceae (Asplundia sp.), Piperaceae (Peperomia rotundifolia), Gesneriaceae (Codonanthe sp.) and various Pteridophytes.

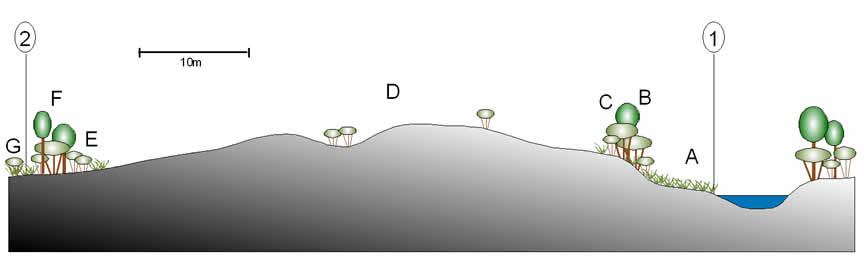

Baixadas and forest streams

Baixadas are depressions in the forest, sometimes containing streams, where the soils are damper than on the surrounding slopes. In lowland regions of the Yanomami area these are often dominated by palm species such as Mauritia flexuosa, Socratea exorrhiza or Jessenia bataua. In the Homoxi region this does not appear to be the case, and most of the baixadas and stream-beds have been substantially disturbed by gold mining. Nevertheless it was possible to observe the vegetation of one apparently undisturbed baixada on the far side of the river from the Homoxi health post.

Although there were a few trees to 30cm diameter and 20 m in height, most of those in the base of the baixada were relatively small (few exceeding 10cm diameter and 10m height). Common trees included Inga spp., Elizabetha princeps, Aparisthmium cordatum and Chrysochlamys membranacea with the occasional stilt-rooted Socratea exorrhiza palm. The shrub and herbaceous layer was denser than in the forest on dry ground on the hills, including Xanthosoma sp., various ferns (incl. Salpichlaena volubilis and Metaxya rostrata), Piper spp. (incl. P. dilatatum and P. glabrescens), Miconia serrulata, M. nervosa, Loreya spruceana, Machaerium sp., Aphelandra macrostachya, Heliconia bihai, Costus sp., Olyra longifolia, Besleria sp., Urera baccifera and Renealmia alpinia. Araceous epiphytes/ climbers (i.e. Philodendron spp.) were abundant, and there were a number of vines present including Drymonia coccinea and Asplundia sp.

|

|

|

Botanical similarity to Xitei

The forest at Homoxi was found to be similar in terms of both composition and structure to that of Xitei, which lies at a similar altitude (620m) and was visited briefly by WM in 1995. Given its relative proximity it is very likely that the species collected at Xitei during that visit would also be found in the Homoxi region. A list of additional species is given in Appendix 4.

Altered environments

Gravels

The most severely altered environments in the Homoxi region are the raised areas of quartzite gravels alongside the Rio Mucajaí and its tributaries. These areas have virtually no topsoil and are generally covered in very sparse vegetation composed mainly of grasses such as Axonopus purpusii, Digitaria sp. and Andropogon angustatus, often in association with a common lichen (Cladonia subradiata).[1] There are usually occasional scattered herbs such as Emilia sonchifolia and Chamaecrista nictitans.

Amongst the gravel mounds are scattered small depressions where shallow deposits of sandy soil have accumulated – presumably washed out of the surrounding gravels by rain. These depressions support denser concentrations of herbaceous species such as Elephantopus mollis (a very common herb in secondary vagatation of all kinds at Homoxi) and occasional shrubs and small trees such as Psidium guajava, Mahurea exstipulata and Clibadium cf sylvestre. Other shrubs/trees occasionally found on the gravels include Clusia grandiflora, Cecropia cf latiloba, Ficus sp., Coussapoa asperifolia There is a considerable amount of insect activity on these gravel areas: many are crossed by a network of leafcutter ant trails, which are clearly visible from the air as white lines.

Apart from the grasses, the most important familiy of herbaceous plants in the gravel areas are the Compositae. These include Acanthospermum australe, Ageratum conyzoides, Bidens bipinnatum, Conyza bonariensis, Elephantopus mollis, Emilia sonchifolia, Eupatorium odoratum, Piptocarpha triflora and a number of other species. Other common herbs include Scoparia dulcis (Scropulariaceae) and isolated concentrations of terrestrial orchids such as Epidendrum ibaguense and Sobralia sessilis. Burned patches are sometimes dominated by Pteridium arachnoideum fern (see below), and another terrestrial fern (Nephrolepis sp.) was found to be common in isolated areas.

|

|

Although the main gravel areas do have some sand interspersed with the quartzite, in some places there are conical piles of pure quartzite gravel that appear not to have changed at all since they were deposited by the garimpeiros. Most of these cones, which are rarely more than 3-4m across, support no plants at all (except for the occasional Pityrogramma fern).

Towards the edges of the gravel areas there are usually patches with shallow sandy soil in which there has been regeneration of shrubs, woody vines or herbaceous tangles. These vary considerably from one place to another. In some areas, for example, there is little apart from a dense thicket of Piper aduncum to a height of 3-4m. In others there is an almost impenetrable vine thicket dominated by the spiny Uncaria tomentosa, or else patches of Baccharia triplinervis and Lantana trifolia. Oreopanax capitatum (Araliaceae) was found growing in one such area, as were patches of the alien grass species Melinis minutifolia (capim gordura). A common component of these thickets is the attractive leguminous vine Dioclea reflexa, which sprawls over the shrubs (or sometimes herbs) in a dense blanket.

|

|

Areas of wetter ground often support large quantities of the fern Pityrogramma calomelanos and, in places, Lycopodium cernuum or Paspalum cf amazonicum. Cyperaceae such as Cyperus luzulae, C. surinamensis, Scleria cf microcarpa and Kyllinga pumila are also common in these damper areas.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 11: Edge of a lagoon in gravel area with dead trees behind |

Figure 12: Camp area of gravels with abundant Pityrogramma ferns |

The forest edge and secondary forests

The composition of the forest edge at Homoxi is variable but includes a typical selection of secondary forest shrubs and trees such as Lantana trifolia, Jacaranda copaia, Laetia procera, Croton palanostigma, Vismia spp., Senna sylvestris, Bellucia grossularioides, Aparisthmium cordatum, Clidemia hirta, Machaerium spp., Leandra sanguinea, Miconia spp., Piper spp., Schefflera morototoni and Solanum spp. (S. rugosum, S. dumosum, S. crinitum and S. stramoniifolium). Palicourea guianensis, with its bright yellow inflorescences, was a particularly conspicuous species in this habitat, as was the common tree fern Cyathea delgadii vel aff. Common vines included Mucuna pruriens, Stigmaphyllon sinuatum, Dioclea reflexa, Cissus spp., Passiflora coccinea, Momordica charantia, Securidaca sp., Mendoncia aspera and Mikania micrantha. Species such as Elephantopus mollis, Desmodium spp., Heliconia spp. (incl. H. psittacorum), Pothomorphe peltata, Costus spp., Scleria secans, Setaria sulcata and Verbesina sp. were present in the herbaceous layer.

Vismia

and Cecropia forests

Vismia species are known to be extremely

persistent and to inhibit regeneration of other species beneath them

(Saldarriaga, 1985). Mesquita et al. (2001) have conducted in-depth studies of forest

regeneration in Central Amazonia, focusing on the difference between secondary

forest dominated by Vismia spp. and

by Cecropia sciadophylla. The conclusions can be summarised as

follows:

·

Clearcut

forest without subsequent use tends to result in Cecropia regeneration, whereas forest that has been turned to

pasture tends to regenerate with Vismia.

·

Regeneration

under a Vismia canopy tends to be

dominated by small Vismia individuals

(many of which are clonal sprouts), whereas regeneration under a Cecropia canopy is more diverse.

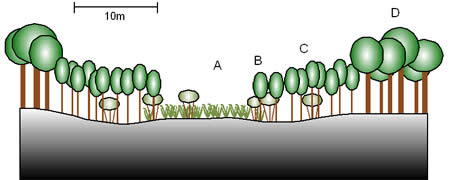

In general the secondary forest on old Yanomami gardens at Homoxi was heavily dominated by Cecropia sciadophylla, clearly visible from the air as an apparently continuous flat canopy. These areas have been burned following initial felling but have not been subjected to the repeated burning cycles and soil erosion associated with the creation of pasture in Amazonia. In addition they are relatively small areas which have never been any great distance from the forest seed bank.

|

|

|

Figure 13: Old secondary forest (Yanomami garden) near Baiano Formiga |

Some of these old secondary forests have now reached a considerable size, individuals of Cecropia reaching 25-30m with diameters of 40-50cm. There are few other large tree species in the canopy with the exception of Croton palanostigma, Alchorneopsis floribunda, Inga spp. and Colubrina(?) sp. However, the understorey is considerably more diverse with smaller trees, shrubs and herbs such as Bellucia grossularioides, Inga edulis, Maprounea guianensis, Elizabetha princeps, Bactris corosilla, Vismia spp., Faramea guianensis, Picramnea spruceana, Miconia nervosa, Psychotria poeppigiana, Piper spp., Costus spp. and Heliconia spp. Woody vines include the common Pinzona coriacea and Bauhinia guianensis.

The Vismia forests at Homoxi tend to occur on areas that have been heavily disturbed by garimpeiro activity, including the edges of airstrips and the margins of the worked gravel areas. The most common species is V. guianensis, which is usually strongly dominant. The phenomena noted by Mesquita et al. (2001), i.e. the relatively low diversity and the preponderance of Vismia regeneration below the canopy, were clearly observable in these secondary forests. They are generally lower (8-10m) and denser than the Cecropia forests, with more slender trees (10-15cm diameter). Small Vismia saplings were commonly observed extending beyond the edge of these Vismia forests in an apparent attempt to colonise the surrounding areas. However, the most distant of these had often been killed by fire or drought.

|

|

Lagoons

Aquatic vegetation in the manmade lagoons at Homoxi was not surveyed in detail. The levels of vegetation vary considerably, depending partly on the depth and the bottom substrate.[2] Most lagoons are surrounded to one degree or another by Ludwigia spp: in particular L. leptocarpa. Shallow lagoons or lagoons with shallows at their margins support areas of Pontederia sp. and, in their shallowest parts (which are probably dry in the dry season) patches of water-tolerant herbs and shrubs such as Begonia fischeri, Aciotis purpurascens, Siphanthera sp., Chelonanthus longistylus, Xanthosoma sp., Costus sp., Hibiscus furcellatus, Centropogon cornutus, Desmodium incanum, Kyllinga pumila, Pityrogramma calomelanos and Piper aduncum.

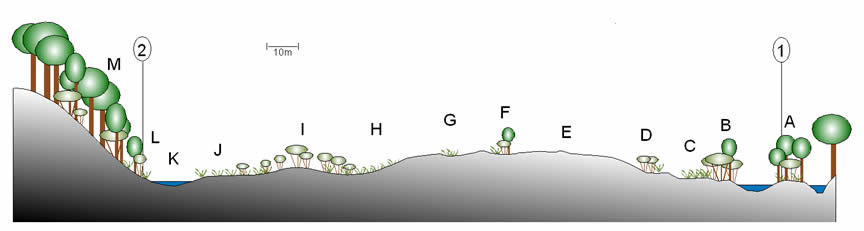

Riverine vegetation

Given the extent of mining activities at Homoxi almost all of the riverine vegetation that was observed was to some extent secondary in nature. In general the Mucajaí is now bordered by open areas covered by a dense tangle of herbaceous or shrubby vegetation with vines. In the places where a high gravel bank borders the river this vegetation is restricted to a narrow strip at its base, the top of the bank sometimes supporting a strip of shrubs or small trees before giving way to grass-covered gravels (see Figs 52 and 53). In other places, however, there is a considerable area of flat land beside the river that is periodically flooded during the wet season and has accumulated silty soil. In these areas there can be large expanses of this type of herbaceous tangle.

The floristic composition of this environment is not dissimilar from that of the edges of the lagoons. Species encountered included Centropogon cornutus, Ludwigia spp., Hyptis cf obtusa, Hibiscus furcellatus, Mendoncia aspera, Palicourea crocea, Cestrum sp., Justicia secunda, Urera caracasana, Besleria sp., Pityrogramma calomelanos, Mucuna urens, Mikania micrantha, Xanthosoma sp., Solanum stramoniifolium, Piper aduncum and Uncaria tomentosa.

This type of herbaceous vegetation probably occurred in small areas beside the river prior to the mining activities, principally on the inside of bends (see Fig. 41). However, the predominant riverine vegetation prior to disturbance would have been forest. These pristine riverine forests, which were not observed directly, were said to have included several species of Inga (including I. edulis and I. acreana), Micrandra rossiana, Micropholis spp., Anacardium giganteum and Pseudolmedia spp.